Introduction

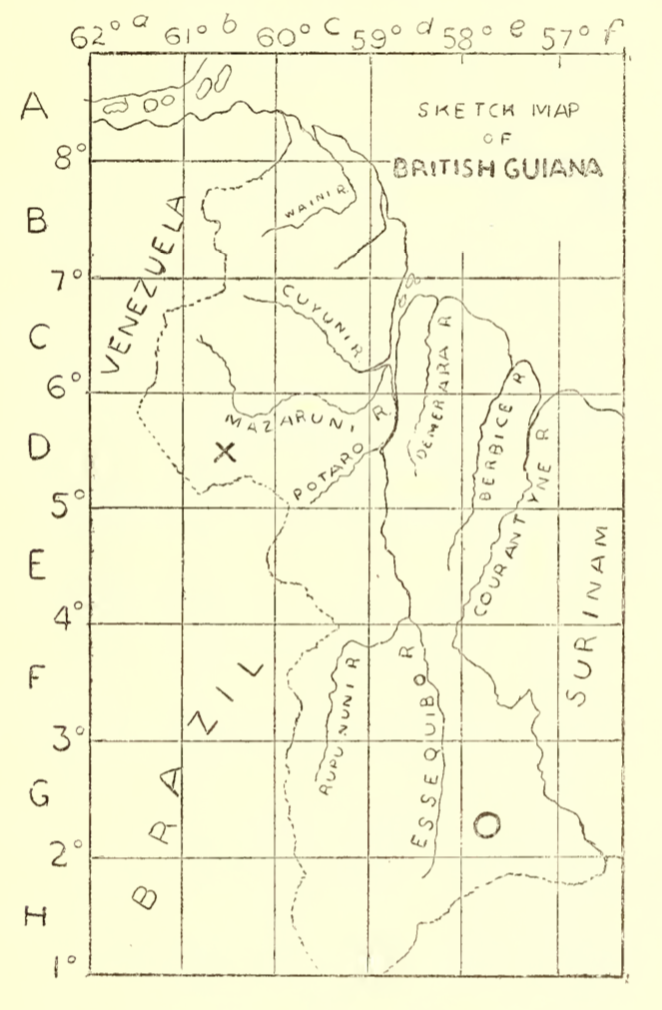

Moritz Richard Schomburgk (1811-1891) participated in the Prussian-British expeditions to British Guiana with his brother Robert. While Robert’s first expedition, between 1835 and 1839, had an exploratory character, the second, in which also Richard was present, took place between 1840 and 1844. In this second expedition, the main interest was the establishment of proper boundaries between current-day Guyana and Venezuela. This issue was a matter of controversy since 1648 when, after years of conflicts between Spanish (the first settlers in the area) and Dutch colonists, Spain recognized the Republic’s independence and also small Dutch possessions located east of the Essequibo River. Throughout the years, the claims over the borderland extended, leading the British Empire (which took possession of the Dutch colonies in 1814) to commission Robert Schomburgk the establishment of clear limits.

As a botanist, his brother Richard took part in this expedition primarily because of his interest in the collection and taxonomy of the flora and the fauna of the region. In his travel, he wrote a three-volume travel journal, which is a rich source of information for those interested not only in the content of his travel but also in broader interpretations meant to understand this content as a product of its time. A first interpretative layer is composed, for example, by the categories through which classifications were made by Europeans in colonial contexts, the rationale behind constructing taxonomies (of the flora and the fauna but also of human groups and cultures), and the state of natural knowledge and cartography in the 19thcentury (how the world was seen at that time by Europeans). As a second interpretative layer, this diary is also a precious source in itself, as printed document, shedding light on how travel diaries were constructed as scientific, social, and literary sources (editing, translation, language, audience), details that can be again inserted in their time in order to be interpreted. This essay aims at dissecting the interpretative layers present in this diary, dividing them in two sections, as shown above. A first layer refers to the construction of the content, inserting Richard Schomburgk in his time and reading his actions as part of broader structure and mentalities, with a particular focus on the themes of slavery and colonialism, taxonomies and scientific racism, healing practices and science. A second layer approaches the construction of this document as historical source, delving into the archival elements that constitute colonial documents.

First layer: Schomburgk as part of his time

Slavery and colonialism

Schomburgk’s positions about slavery are contradictory and ambiguous. On January 1817, the population of enslaved people was 77,163 for the Essequibo and Demerara districts, and 24,529 for the Berbice, while the rest of the population amounted to 8,000 (Schomburgk, 1922 [1847], p. 21). On August 18th1823, an emancipation rebellion blazed into flame, with enslaved people demanding their freedom by force. Only 2,000 people faced the military power (while 13000 people were involved in the uprising, see da Costa, 1994), and in few days colonel Leahy crushed the insurrection. This was not the first episode of revindication of rights and freedom for the enslaved people (in 1763 Berbice saw the longest-lasting slave rebellion in the Caribbean, see Lee, 2011), but it was, according to Schomburgk, the last attempt to obtain freedom by force.

This narration of the facts is followed by a more personal view in which Schomburgk expresses his perplexity about possible effects of this emancipation:

It was to be feared that the temporary effects of Emancipation could only be detrimental to the economic and manifest welfare of Guiana […] All the labour supply lay in the hands of the African slaves and, owing to the conditions and prevailing climate was the only source to be tapped. The sudden and unprepared for transition from the condition of a slave who had no will of his own to that of a self-determining free citizen was one of the most powerful means of promoting the in-born and hereditary indolence of the negro. Work had hitherto only been a burden to this hitherto despised and ill-treated class who, forced by the rod of correction, had to submit to it: Emancipation granted him the unalienable right over his own destiny, and at the same time the liberty to give free scope to his in-born tendency to habitual idleness […] The European labourer thanks the man who gives him work: the free negro on the other hand, in addition to his pay, asks his employer to thank him for dedicating his services to him. (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 22-23)

It is interesting to notice that these comments are written after the Emancipation already occurred (1833-34) and after the end of the Apprenticeship period (1838). In fact, the argument proposed by Schomburgk, for which it was difficult to think that enslaved people would have been able to take care of themselves once free, was the leading argument adopted by the supporters of the apprenticeship, a transition period between slavery and freedom, meant to teach how to be a free person. These beliefs were still engrained in Schomburgk mentality, his words perfectly representing the idea behind these projects of subjugation. In order to understand the components of this mentality, it is possible to dissect his thoughts in two themes, the in-born and hereditary indolence andidleness and the unalienable right over his own destiny, with the first justifying the unthinkability of the second. In this passage, Schomburgk promotes a biological racist perspective, for which enslaved people are in their condition because of their inner and hereditary attitudes, something for which they deserve to be distinguished from those who are, appropriately, free (i.e. the Europeans).

In other occasions, though, he discloses humanistic views, in contrast to these moral judgements, where enslaved people are not considered as inferiors but deserving of respectable treatments. For example, he identifies slavery as “that dark spot in the history of mankind” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 46), or he paternalistically expresses pity, denouncing the procedures enacted by the police to suppress the widespread costume of cock-fighting as “more than tyrannical, since they [the “poor devils”, that is the owners of the cocks] were being treated not as human beings but like refractory brutes.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 51) The two perspectives, though, that of moral judgements and paternalism, are not necessarily in contrast, for it was not uncommon to compare Africans to children, as shown above when discussing the ideas leading apprenticeship, with enslaved people not able to be independent, and white people seen as educators.

How can these two opposite visions about slavery coexist in a single individual? Two explanations could be put forward, considering his position within a broader colonizing project and within debates about abolitionism. To begin with the first point, civilization is part of Schomburgk’s mentality since the beginning of his travel. After a brief stay in London, he left Europe on the 18thDecember 1840, and his words of excitement, approaching the American continent, can be read as a declaration of intents: “The land I had yearned and longed for, the land of fairy fancy of blood and terror, of the most effulgent hope and expectation for the people of Europe, the land where the dignity of man has been trampled under foot so long, but where now is risen a modern era which is already illumining the distant Future with its initial brilliance – the American continent stretched out before me.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 14) In its colors, this sentence highlights the civilizing mission that Schomburgk adhered to. Expression such as fairy fancy, blood and terror, and dignity trampled under foothighlight an exotic imaginary and a brutal and animalesque idea of the people living those territories. The Future is capitalized as to indicate the improvement, the spirit of freedom that will be brought by the modern era expecting them, while the illumining and the brillianceare terms indicating the main director of this project: the Enlightenment. This is a motif often times recognized by colonial scholars as one of the main reasons behind colonialism. (Go, 2016, p. 29)identifies three themes, linked to the Enlightenment, promoting the imperial episteme: humanism, universalism, and positivism. “[H]umanism maintains that there is ‘a universal and given human nature [i.e., ‘Man’]’ that can be known and improved on the basis of Reason […] universalism [regards] the notion that the world can be fully known and understood in terms of basic truths independent of space and time. By this view, not only does Reason allow us to access truths, but those truths are applicable everywhere. Furthermore, humanism and universalism both depend upon a notion, largely traceable to Descartes, of ‘objective’ and ‘impartial’ observers who are themselves unconstrained by space and time […] positivism [regards] the set of philosophies that reject metaphysics and heralds Reason, and its presumed practical form of the ‘scientific’ method, as the best approach for knowing human nature and the world in general – if only so that humans can control both.” In this sense, Schomburgk’s position resembles that of the broader project he was a part of, where enslaved people are seen as inferior because of biological features, but still humans that can be civilized and enlightened. What is generally despised by him about slavery and the relationships of power (for example the repressive actions of the police) is more the brutality and the violence with which they took place, rather than the underlying project behind them.

A second explanation for this discrepancy might be put forward considering the debate about the causes of slavery abolition. With the publication of Capitalism and Slavery (Williams, 1944), Eric Williams started a discussion about a possible declining thesis as explanation for the rise of the abolitionist movement. In this book he maintained two main points: “that profits from the slave trade […] provided most of the capital that financed the English Industrial Revolution” and that “the rise of British abolitionism [was linked] with an irreversible economic decline of the British West Indies, both as tropical producers and as importers of British goods” (Davis, 2010 [1977], p. xiv). The theory of decline raised a heated debate about the reasons of abolitionism, with Drescher’s Econocide(2010 [1977])as one of its harsher critics. The counter-argument proposed by Drescher is that the “Anglo-American expansion of the slave trade was prevented not by market forces but by a major transformation in Anglo-American public moral perception, spearheaded by a small group of abolitionist reformers” (Davis, 2010 [1977], p. xvii). The debate is complex, and I will not try to find evidence for one side of the story or the other. What is relevant to notice here is that it could be plausible to think of Schomburgk as close to the abolitionist movement (idea present in several passages of his travel journal, such as the depiction of slavery as “that dark spot in the history of mankind” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 46), as described above), something to take into account when considering the apparent duplicity of his opinions about enslaved people and slavery as a project. One the one hand, his positions about enslaved people belonged to the time and colonial project in which he was a part of; on the other hand, his repulsion toward violence and exploitation could have been expression of humanitarian concerns typical of the civil society described by Drescher.

This humanitarian perspective becomes even clearer when Schomburgk’s opinions also about Amerindians are taken into account. In describing their relationship with the Colonial Government, he uses harsh words to denounce the unfair and exploiting treatment reserved to them: “owing to this treatment and exploitation of the harmless aborigines on a basis of the meanest selfishness, whereby they had to perform the hardest woodcutting tasks on the timber grants, months at a time, for a few worthless glass beads, labour of the most serviceable nature has been lost to the Colony […] The Colony owes the poor neglected Indian an old-time heavy debt, the present-day repayment of which is not to be expected.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 53-54) Thus, Schomburgk does not blindly take part in the colonial project; rather, he recognizes its limits and the problems intrinsic in its exploiting mentality.

In this reading, humanitarianism, that is the recognition that every person has certain rights independently on contingent or ascribed factors such as race (distinct from, but complementary with, colonial humanism as described above by Go), is an important force leading Schomburgk’s opinions. In both the cases of African’s slavery and Amerindian’s colonial exploitation, dignity and honesty of treatment are the two moral concerns that emerge the most. Several questions stem from these considerations: what was the impact that colonial diaries, such as Schomburgk’s, had in European societies? Were they vehicles for the formation of moral concerns about human rights in the public sphere? Colonialism, in this perspective, could be seen not only as an economically and politically exploitative enterprise, but also as a step in the construction of contemporary European civil societies. On the other hand, this reading could be problematized considering the actual audience that Schomburgk was aiming at or the one that ended up reading his works. If botanists or scientists in general were his main audience (I would rule out an exclusivity of his documents for the British Empire, given that his travel notes were published by the publishing house of J.J. Weber (Leipzig) who published illustrated works in the field of natural history and popular education[1]), a spill over into the broader society would be less likely. In both scenarios, the question of whether and how the colonial experience shaped the European civil society in its moral components remains cogent.

Taxonomies and scientific racism

Even though humanitarianism could be seen as an important moral characteristic of Schomburgk, his biological racism remains uncontestable. Moreover, as shown above, this position could also be not at odds with his concerns about treatment of enslaved people and Amerindians, because of his civilizing and paternalistic mentality. It should be taken in mind that Schomburgk was a botanist, not a missionary. In other words, his main aim was not to convert or to “civilize” Amerindians; he adhered to this system of thought without an active part on the ground. Nevertheless, writing a travel journal for the general public where these positions are held and put forward might still have a colonizing effect, because of the effect that the reproduction of colonial ideas had spilling over from single colonizers to a broader audience. In other words, the mental categories with which Schomburgk approached the Americas, even if just as a botanist, could still be part of the colonizing project, reinforcing its fundamental categories, especially if his diary was meant for the broader European public. What was his contribution in this sense? How did he take part in the colonial project as botanist?

Taxonomies of plants, animals, humans, and cultures are constant presences in Schomburgk’s travel notes. The first two are the most frequent ones, with detailed excursions about colors, shapes, and smells of the blooming flora as well as shapes and behaviors of the fauna. For what concerns classificatory efforts about humans and cultures, there are many instances in which brief and descriptive considerations are translated into articulated positions justifying relationships between people and broader civilizing trajectories. A clear example of this transition and transposition emerges in the reasons put forward to justify the decline in cotton export. Discussing the economic relationships between the colony and the British Empire, he states: “In contrast with this huge quantity of Imports, Export is limited solely to sugar, coffee, rum, syrup and an inconsiderable amount of cacao. The former very extensive export of cotton has sunk to nilsince Emancipation, because the material obtained by free men cannot compete with that won by slave labour.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 35) This last sentence is key in explaining the transposition from objective conditions (decrease in exports of cotton) to subjective justifications (idleness of the enslaved people). On the one hand, these words can be seen as a racist justification for the cause of this decline when rephrased as “this decline is an additional confirmation of the innate laziness of slaves: once left free, their predispositions emerge, leading to a loss of productivity”; in this case, the justification is biased by racial prejudices (without negating that there might have been lazy people among the workers, generalizing attitudes on the basis of racial categories can be seen as a definition of racism). On the other hand, this justification might be the actual cause of this decline because of a self-fulfilling prophecy: prejudices about enslaved people were diffused among traders, and once the emancipation project emerged, the value of the product declined because of these ideas. In both the cases, the racist attitudes emerge when considering the actual explanations for this decline, which have nothing to do with race, but more with socio-economical reasons: world market prices for cotton fell in the 19th century after the US South (after the invention of the cotton gin in 1794) started to produce a different variety of cotton more cheaply and in great quantity, with which Guianese cotton could not compete. Hence, planters shifted to sugar instead. The only reason linked to the condition of laborers is physical exploitation: it is possible to extract more labor with a whip, hence production was higher before emancipation.

Moreover, biological distinctions were not only made between whites and blacks, civilized and uncivilized, but also between Amerindians and enslaved people. Even though Amerindians were subject to derogatory terms and descriptions, for example, that they had a penchant for alcohol, or were filthy and unclean, they are often considered as better than the enslaved people. A moral hierarchy is established in words as “an Indian, as a workman, is worth double a negro” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 53), or “the essential difference separating the Indian character from that of the Negro […] Our Indians bore the pangs of hunger in silence with stoic steadfastness […] The majority of the Negroes and coloured people on the other hand, what with cursing and sweating, had downed paddles about midday” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 168), or establishing hierarchies among the Amerindians people themselves, some with “a higher state of civilization” than others (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 120). In Schomburgk’s writing, what defines a higher or lower stage of civilization is not clear, even though cleanness and manners are often times taken as motives to talk in these terms. Nevertheless, comparisons are very frequent.

In this perspective, a mental disposition typical of the time could be detected in Schomburgk’s mentality, that is the idea for which humans could be classified on the bases of their physical and physiognomic characteristics, in the same way as plants or animals. This idea derives from physicians and doctors as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840), and James Cowles Prichard (1786-1848), whose works in craniometry and pigmentation established the scientific study of races. Moreover, these first steps relied on already established systems of classification, developed by naturalists and botanists as Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788) and Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). In this way, race was constructed as “a hybrid political, economic, religious, and social construction that, from the 1770s onward, also had a healthy life in emerging disciplines of moral philosophy, natural history, and comparative anatomy.” (Wheeler, 2000, p. 307) This naturalistic approach to the study of race was soon flanked by moral and cultural considerations: “The skull, they believed, was supremely suited to signify difference, because the brain and the privileged organs of sense were lodged in it […] The myriad forces encouraging the selection of the mind as the privileged organ of sense range from Christian tradition, humanism, Lockean psychology, and the Enlightenment value placed on reason to the belief in moral choices being able to ameliorate the effects of climate.” (Wheeler, 2000, p. 313) As highlighted by Pels (1997, p. 175), “Statistics and ethnography were the carriers of modern classifications of race, nation, and ethnicity […] Human beings were simultaneously redefined as analogous to animal and plant species, as ethnic types to be slotted in the pigeonholes of such questionnaires.” This had not only scientific advantages, but also governmental ones, because census and statistics helped supporting colonial control and governmentality (Anderson, 1991, Cohn, 1987). In other words, scientific racism was not only the possibility to conceive race as category with which to scientifically define and categorize people, but also the attachment of moral judgements to these human taxonomies in order to foster relationships of power and exploitation.

Schomburgk was aware of these systems of classification. In his digressions about the flora and the fauna of the region, he often times reports the Latin name of the specie he is describing, explicitly referring to the Linnaean taxonomy with the abbreviation “Linn”. When it comes to describing enslaved people, Amerindians and their customs, he never mentions Blumenbach or Prichard. Nevertheless, following the explanation given so far about the relationships between botanical and anthropological taxonomies, similar steps seem to have been followed also by Schomburgk: “So far as size is concerned, the figures of the Arawaks differed but little from that of the Warraus, as they do not exceed the average man’s height: but as regards shape as a whole, they varied more. The whole bodily frame was much better proportioned: they were indeed not so muscular as the former, but on the other hand, shewed themselves much smarter in all their movements, far more active and far more agreeable. The colour of their skin was much lighter, the features on account of their regularity were more expressive and owing to the more marked tattoo had assumed a peculiar character” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 116), or also “The build of body and whole appearance of the Warraus, their uncleanliness and indolence, I have already sketched in previous accounts: their inner nature completely corresponds with their outer appearance: their eyes and features only too distinctly show that their intellectual faculties are still slumbering.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 126)

Is this a description guided by direct knowledge of the Amerindians, or by widespread stereotypes? Does Schomburgk use a yardstick to compare different people (Africans, Amerindians, Europeans) to evaluate degrees of civilization? The answer to the first question is complicate, since the degree of uncleanness and indolence, as mentioned in the citation above, is bound to comparisons based on what is clean and unclean. Hence, the first and the second question are strongly intertwined. Schomburgk has seen and lived with different Amerindians, since this is explicitly mentioned in his notes. What is less explicit, and open to further inquiries and interpretations, is the degree to which stereotypes have shaped his ideas. The lack of systematic efforts (at least in his notes) to define what is civilized and the necessary characteristics to be considered as such makes me penchant to attribute a heavy weight to stereotypes as guides for his thoughts. Moreover, it could be plausibly proposed that the yardstick of civilization was Europe (which might be considered, again, as a product of positive stereotypes for his ingroup). In the passage above, there are explicit clues pending for this interpretation: the proportion of the body, smart movements, a lighter skin, eyes as indicative of the intellectual faculties are taken as indicators of a superior race compared to the other. With proportionality as embodied in the Greek classic statuary, a lighter skin as a marker distinction between Europeans and the rest of the world, and rationality as lynchpin of the Enlightenment project, the European people seem to be the ideal model upon which other people are compared with. In this categorization, it is relevant to notice that not only physical characteristics are evaluated (such as the color of the skin) but also intellectual and moral (such as the eyes as source of rationality).

Healing practices and European meanings

Another sphere where the influence of European categories were particularly influential in Schomburgk’s narration is medicine (broadly conceived as system of practices with which to cure diseases and illnesses, including both Amerindians’ healing practices and the European medicine). During his travels, Schomburgk often encountered different types of medical problems, from serious disease (fever) to small but annoying issues (such as small insects under the feet’s nail). In his narration of the cures he received and assisted to, what is most interesting from a colonial point of view is, on the one hand, the description he gave of healing practices and their relationships with cultural and religious beliefs, and, on the other, his report of the perceptions Amerindians had about Europeans in their (of the Amerindians) medical environment. When different systems of beliefs enter in contact, the main question is whether and how situations of cultural transposition, the imposition of European signified (meanings) over other cultures’ signified (practices), are at play. The following section addresses this question with a specific focus on healing practices.

According to Schomburgk, the religious system of Warrau and Arawak is based on spiritism and totemism. Spirits are present in every moment of people’s life, and they can be roughly divided in two categories, Good and Evil. While Good is a “single Something, and though it indicates its presence in different forms […] there exists only one Beneficent Being” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 131), Evil is heterogeneous in its expressions, authors of diseases and hardships. Hence, human life is intrinsically intertwined with that of spirits. In one occasion, the narration of a feast starts with music and dances meant to banish the evil spirits, something which is described as “exorcism ceremony” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 131). The use of this term is curious, and hides a possible source of cultural transposition operated by Schomburgk. In fact, while the actual presence of spiritual possession among Native Americans is controversial in the anthropological literature (Stewart, 1946), defining the ceremony as exorcism means identifying a duplicity between the spiritual world and the humans, with spirits going out of their world and entering our world (and body), distinction which might be the fruit of a European religious view. The main concept underlying this issue is that of cultural transposition, where European signified (or meanings) are imposed over Amerindians signifiers (what is here called exorcism). As in many other occasions, the lack of an insider point of view, that is of Native Americans themselves, leaves this question unanswered.

Nevertheless, I think it is possible to gather further details about this issue looking at those situations that involve practices of medical healing. In fact, according to Schomburgk, religious beliefs and medical practices are a unicum among the Amerindians, with a figure, the Piai, being both spiritual guide and man of medicine: “Amongst all mortals, the power is alone granted to the Piai or sorcerer, through his secret arts, to counteract these damaging influences or to remove them to a distance […] The Piai is also priest, doctor, and sorcerer at one and the same time, a powerful and feared individual who has it within his control whether to allow the persecution of his subject spirits to run a free course, or to grant protection from their influences.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 131-132) In describing the typical course of action taken by the Piai in healing someone, Schomburgk again uses the concept of exorcism, to stress the spiritual nature of Good and Evil episodes in human life. Two instances, though, could reveal a more subtle opinion guiding his perspective. On the one hand, patients are directly involved in their own healing through an act of imagination(“The invalid’s imagination now completes the cure”, Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 133); on the other hand, if the healing does not work, the Piai saves his faceburying the rattle used in the exorcism together with the dead patient, because “it has henceforth lost its effects, the curative agency of the magic remedy dying with the invalid.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 133) There is a discrepancy here between a narration from an external spectator, who reads certain actions through familiar (to him) categories, and the beliefs of those whose actions are narrated. It could be argued that the Piai does not want to save his facewhen one of his patients dies, because this would imply a dissonance between what is believed and what is real. In other words, while Schomburgk, as external spectator, might have doubts about the presence of spirits and the justification of certain medical practices based on a battle against these spirits (hence, the terms exorcism, imagination, save the face), Amerindians belong to this religious system, with no pretending in the Piai actions.

Hence, in situations like those described above, it is possible to lean for a cultural transposition thesis, for which medical practices were read through European categories, creating doubts and sense of artificiality. On the other hand, though, there are occasions in which Schomburgk expresses transcultural respect about Amerindians practices, with this term meaning the avoidance of reading through a personal lens certain practices. There are various instances in which he describes the idea for which poisons and medical compounds should not be prepared in presence of Europeans, in order not to contaminate them. Other times, the ingredients are not even revealed when he asked. Another important instance revealing Amerindians’ skepticism about Europeans is in the training of the future Piai: “During his apprenticeship he is not allowed to come into any contact with Europeans, as he would thereby lose his influence over the spirit world for evermore.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 331) Therefore, there is the idea for which Europeans cannot enter in contact with the religious world of the Amerindians. This might have various interpretations: from an insider perspective, for example, a European intromission could interfere with the spirits, making them angry or causing the loss of power in tools such as the healing rattle; from an outsider point of view, it could be that a system of beliefs is as such because the boundary between beliefs and reality is blurred. As seen before, it is likely that Europeans, with different systems of beliefs, perceive the Amerindians’ as constructed (hence, beliefs instead of reality). In order to be effective, poisons, medical compounds, and religious training have to be real, and not beliefs. For this reason, external interferences might hinder this effectiveness, tearing apart the veil between reality and beliefs. In this regard, Schomburgk shows respect for this attitudes, without using them as a way to derogatorily depict the Amerindians.

What emerges from this section is the heterogeneity with which different systems of beliefs enter in contact with each other. On the one hand, instances of cultural transposition by Europeans are frequent in colonial contexts, as the example of the Amerindian ritual read by Schomburgk as an exorcism shows; on the other hand, Amerindians have their own readings of colonialism, and cultural adaptations, such as the rules for religious training, reveal important interpretations of colonial interferences (without forgetting that, in order to have a genuine perspective about Amerindians adaptations to colonialism, relying on colonialists’ reports is not enough, and Amerindians sources, whether written or not, should be taken into account). Medicine and healing practices are at the core of a bundle involving the health of the soul (religious beliefs) and that of the body. Because of this position, full of symbolic meanings and interpretations (e.g. term exorcismmight have different meanings between Europeans and Amerindians), medicine in colonial context is a crucial turf to explore in order to understand the symbolic forms with which colonialism unfolded.

Second layer: colonial documents as archival sources

After having dealt with the content of Schomburgk’s travel journal, I will now interrogate its envelope. That is, I will consider the conditions under which this document was published, inserting it into a broader perspective about colonial documents, and reflecting upon the possible ways in which what I here call the second layer might have influenced its content (its first layer).

The first edition of this travel journal was published in 1847 by the publishing house of J. J. Weber (Leipzig), and the edition I have relied on was the English translation by Walter Roth (published by the Daily Chronicle Office, Main Street, Georgetown in 1922). As the first page of the English edition reports, Schomburgk’s work was “Translated and edited, with Geographical and General Indices, and Route Maps by Walter E. Roth” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. i). Moreover, at page ii of the Geographical Index, the editor highlights that the maps were not present in Richard Schomburgk’s original notebook, but were “based mainly on the results of Sir Robert Schomburgk’s discoveries” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. ii). These two pieces of information, the translation from German to English, but also the re-adaptation in its content for what concern geographical and general indices, and route maps, provide a first terrain of enquiry about the scope and the format of the original document. There are two important aspects to consider when evaluating this process of editing, namely the method of writing of the original travel journal, and the audience which the journal was meant to reach.

For what concerns the style of the original documents, it is likely that, given the nature of Schomburgk’s travel, he wrote his thoughts and experiences using pen and paper, instead of a typing machine. This might explain the lack of coherency in his writing, with many themes and situations most of the time present on the same page. Some questions arise from here: if the English edition (thus, edited and translated) has some degree of contradiction, how does it differ from the original document? Was it made as much coherent as possible in order to have a narrative structure and reach a broad public? In addition, hand-writing has many inherent problems of readability, and loss of information due to deterioration. Hence, in approaching a printed copy (in this case the first German edition), the first issue that should be addressed is the accuracy with which the original text is reproduced. How much of the original document was revisited in order to make it a readable and publishable book? The issue becomes even more complex when a second editing is performed, that is the translation from German to English. Problems of meanings and interpretation are always present in every translation, but in this case the translation can be particularly problematic for the message transmitted with the journal. In fact, in the previous section, I have mainly focused on interpretative analyses of words and sentences, such as exorcismand idle, terms charged with meanings which are not only derived by the narration in which they are inserted but also by the narrator who uses them. In this case, the question is where can the boundary between Schomburgk and his translator be drawn? To whom are these terms attributable? What if Schomburgk has used the German term Beschwörung(meaning exorcism but also incantation, invocation, entreaty) instead of the less ambiguous term Exorzismus? What if the English translator has imposed his colonial categories and some of the critiques emerged in the previous section were mainly the result of translation rather than actually present in the German (or even in the original) version? A bilingual analysis of the original document, as well as an historical contextualization of the editor and translator’s positions about colonialism can provide answers to these questions. For the moment, I think it is important to highlight that when reflecting upon the meanings embedded in a colonial text, it is fundamental to interrogate the production of that text, tracing its publication and editing history.

A second element to take into account is the audience to whom the journal is directed: was it meant for a group of specialized botanists, of amateurs, for the general public, or for British officials? As proposed above, this question should necessarily be posed after having detailed the relationships between the original and the edited document, as different editions might have adapted the text to make it more accessible for a broader public or they might have inserted more technical details (such as geographic maps and indexes) in order to help specialists (botanists, geographers, anthropologists) tracing the journey and contextualizing the information provided in the text. Aside from these considerations, that cannot be addressed here, is it possible to derive some clues from the text in itself about its audience? My opinion is that Schomburgk’s initial idea was to present his journey to two types of public: a group of botanists, and the general public. The first volume’s preface begins with the explicit intent to write the journal for these two audiences: “While submitting herewith to the Public the results obtained during my stay in a part of South America […] The results obtained in almost all departments of the several branches of Natural Science in the course of the travels undertaken by my brother, Robert Schomburgk, under the direction of the Royal Geographical Society in London […] had attracted the attention of men of learning in the homeland.” (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. i) To the botanists, Schomburgk has reserved an entire volume, the third (not even translated from the German, something highlighting that a translation was meant to reach a general, and not specialist, public), exclusively containing botanical information about the flora he has collected or seen during the travel. In parallel, the first two volumes are a mélange of styles, sometimes with passages containing detailed and technical specification about the flora and the fauna, with Latin names and specification of their physical characteristics and properties, paced by more narratives passages, as if he was a novelist (the translator himself compares Schomburgk’s style with that of novelists as Waterton or Defoe, see Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. i):

Over there [in Europe] every inch of land called to the wanderer “I am subordinate, subject to human intelligence.” Out here [in Guiana], however, Nature was loudly proclaiming in her unrestrained liberty, “I still rule with my original strength unimpaired.” Over there, break of day awakens the life that has hardly fallen asleep, and what with boat pressing after boat, the splashing of the busy oars that beat time to the joyous matutinal greeting of the lark, and the half-hidden hamlets peeping pleasantly from out of the dark green of the vine-clad heights—there is but very little of Nature remaining to be seen anywhere. Over there, large two-masted ships push off from their anchorage and follow the old highway while the herdsmen drive their cattle, with tin1 cheerily tinkling bells to the water, and the ruins of the Past either look down in sombre gloom from the mountain tops or else are reflected in the ever-youthful never-aging current: in short, civilisation yonder has spun a multiplicity of interests around human life and is prepared to lay Nature waste over a still wider area. But here? Everything the reverse. The eye searches in vain for testimony of creative human intelligence, of the transforming powers of man, but only recognises the works of Nature labouring with inconceivable prolixity; for here, even Man himself who is still the true image of her handiwork has not yet freed himself from her bonds, nor yet risen superior to her sway. (Schomburgk, 1920 [1847], p. 256)

In this perspective, the adaptation of certain styles to the audience of reference can be critically seen as a way in which colonial categories were normalized and introduced into the collective imaginary of the European audience. The exoticization of colonial travels is what Said has described as Orientalism, that is the idea for which the process of European domination over the Orient is guided by three ideas: “First, there is the idea that the world is divided (polarised) into two camps, Europe and the Orient; second, Europe has defined itself over against the Orient which for Europeans constitutes ‘the other’ – something which is in essence, different, abnormal and inferior; and third and most important, European knowledge of the Orient was for the purpose of sustaining or increasing European power and dominion over the Orient.” (Oddie, 1994, p. 27) In other words, making the travel palatable to a European audience through the appeal to exotic notions such as the mysterious, flourishing, and unconstraint Nature, can be seen as a narrative escamotage to create fascination and curiosity for the unknown, but also as a way to justify Enlightenment projects, in order to civilize wild territories (and people).

In order to understand a colonial document not only for its content but also as a product of its time and as a creator or perpetuator of certain narratives, this paper has shown that it is crucial to interrogate the various layers composing its structure. Moreover, these levels of analysis are interrelated, for even when the content is critically approached and dissected, perusing the characteristics that make a document as such (the style, the audience, the edition, and the translation) gives the possibility to see under a new light already analyzed details and passages. In other words, the work of social scientists interested in colonialism and postcolonialism cannot prescind from the treatment of colonial documents first of all as historical document, contextualized within a fabric of meanings and narratives that have to be untangled in order to be understood and used as sources of analysis.

Bibliography

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism.London: Verso.

Cohn, B. S. (1987). An Anthropologist Among the Historians and Other Essays.Delhi: Oxford University Press.

da Costa, E. V. (1994). Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood. The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823.Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press.

Davis, D. B. (2010 [1977]). Foreword. In S. Drescher,Econocide. British Slavery in the Era of Abolition(pp. xiii-xx). North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

Drescher, S. (2010 [1977]). Econocide. British Slavery in the Era of Abolition.North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

Go, J. (2016). Postcolonial Thought and Social Theory.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee, W. (2011). Empires and Indigenes: Intercultural Alliance, Imperial Expansion, and Warfare in the Early Modern World.New York: New York University Press.

Oddie, G. (1994). ‘Orientalism’ and British Protestant Missionary Constructions of India in the Nineteenth Century. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 17(2), 27-42.

Pels, P. (1997). The Anthropology of Colonialism: Culture, History, and the Emergence of Western Governmentality. Annual Review of Anthropology, 26, 163–183.

Schomburgk, R. (1922 [1847]). Travels in British Guiana.Georgetown: Daily Chronicle Office.

Stewart, K. (1946). Spirit Possession in Native America. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 2(3), 323-339.

Wheeler, R. (2000). The complexion of race: categories of difference in eighteen-century British culture.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Williams, E. (1944). Capitalism and Slavery.North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

[1]https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Jacob_Weber